Welcome to Our Women Through History homeschool Course

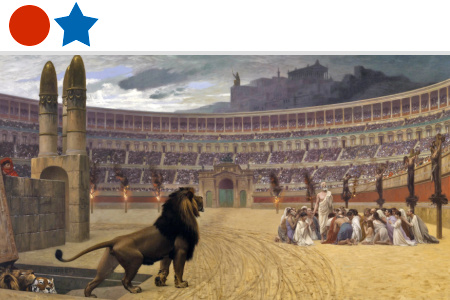

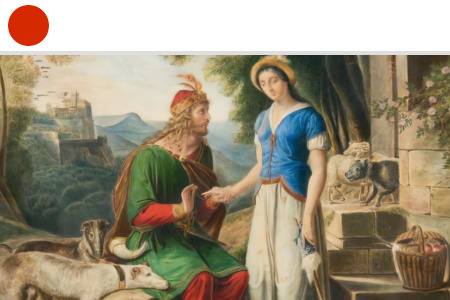

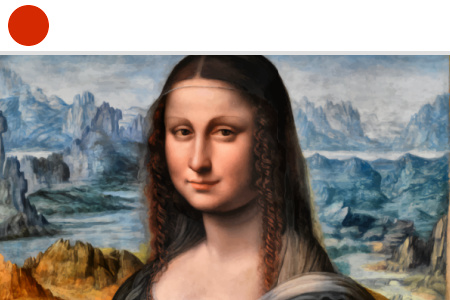

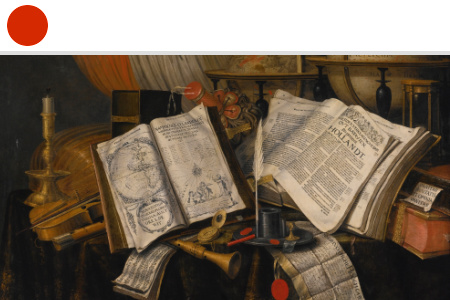

What role have women played in history? Women Through History investigates how women, whether powerful or peasant, have impacted the world since ancient times. For twenty-nine weeks, middle and high school students use historical art, maps, recipes, and writings from women to discover what life was like for women of the past.

Stay organized and confident in your homeschool journey with the Homeschool Records Center and Schoolhouse Gradebook. Simplify record keeping, track progress, create transcripts, and meet state requirements with printable tools and expert guidance—all in one convenient place.

External links may be included within the course content; they do not constitute an endorsement or an approval by SchoolhouseTeachers.com of any of the products, services, or opinions of the corporation, organization, or individual. Contact the external site for answers to questions regarding its content. Parents may wish to preview all links because third-party websites include ads that may change over time.

Para traducir cualquier página web, haz clic en los tres puntos o líneas en la esquina superior derecha de tu navegador, o haz clic aquí para más información.

Women Through History

Length: 29 weeks

Content type: Text based

Grades: 8–12

Kaitlyn Sexton

Related Classes You May Enjoy