More About Our American Folklore Homeschool Language Arts Course

Where would a nation be without its stories? To have a sense of identity and progress, to understand how it has become what it is today, every nation must know its past. History is composed of many elements—events, memorable dates, important people, and political upheavals, for example. Together, these elements make up a nation’s story.

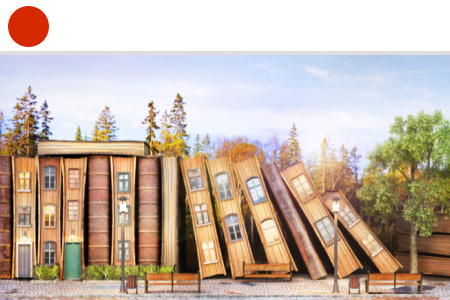

Beneath that history, however, is a fascinating picture. Think of it as a kind of tapestry woven by the nation’s people with brilliant threads and intricate details. Sadly, though, this tapestry is often under-appreciated. Without taking the time to examine and enjoy it, people miss a delightful, informative window into the lives of the people who helped to shape a nation’s history. This tapestry is called “folklore.”

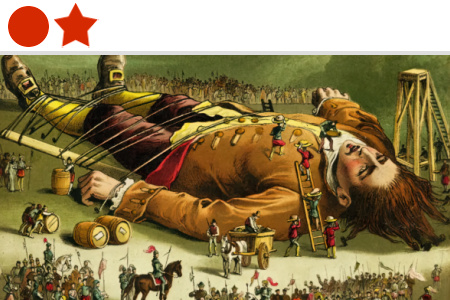

This American Folklore homeschool language arts course divides the country into six regions which are covered systematically after an opening study of American Indian folklore. Within each region homeschool middle school and high school students focus on one or two kinds of folklore, in order to better understand the nature of folklore, and highlight “folk music of the week” (instruments, songs, and dances). At the beginning of each region, students discuss one aspect of American folklife, such as holidays and ethnic traditions. It’s important to remember, though, that the different types of folklore don’t belong just to America. They have been around much longer than America has. Because the America recognized today was settled by immigrants, the roots of national folklore are not only in the New World, but also far, far away in the Old. Thus, folklore connects people to a heritage as Americans, to be sure, but also to a heritage in other nations across the oceans and the ages.

American Folklore homeschool language arts lessons include (but are not limited to) the following topics:

- American Indians—mythology*, fables

- Northeast—legends, spooky stories*, and epitaphs

- Appalachia/mid-Atlantic—nursery rhymes, oral history, sea chanties

- Southeast—spirituals, animal tales, trickster tales

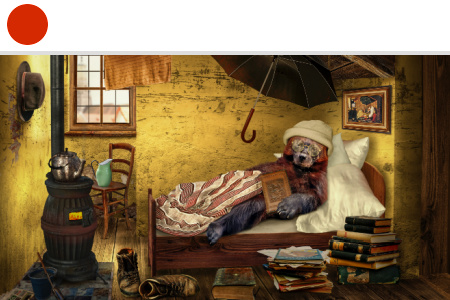

- Midwest—fairy tales, weird place lore, folktales

- West—cowboy lore and ballads, Spanish spiritual stories, fabled creature sightings

In addition, at the end of the homeschool language arts course, students have the opportunity to choose a final project to complete that will pull their studies together. For example, the student might create a scrapbook of their family’s oral history—perhaps recipes handed down from grandmothers, stories of their parents’ childhoods, games made up in the backyard with siblings, and so on.

Ready? Get started exploring heritage through American folklore!

*Some parents may be understandably concerned about the inclusion of mythology and spooky stories in this course. Because a study of folklore would not be complete without attention to these sub-genres, they are included. Parents are encouraged to use the course in whatever way they see fit, even if that means skipping a lesson or two; however, it is important to note that these types of folklore are taught only from a neutral, academic perspective.